Peptides for Bodybuilding

Peptides for Bodybuilding: Does it Actually Work?

More athletes, bodybuilders, and gym-goers have taken an interest in using peptides for muscle growth, fat loss, and even increasing appetite when bulking. The main peptides used for building muscle mass and enhancing body composition are known as growth hormone secretagogues, specifically growth hormone-releasing peptides (GHRPs) and growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) agonists.

What are Peptides? Peptides, a popular category of supplements, stimulate the production of essential hormones needed for muscle growth and optimal gym performance, resulting in hypertrophy. These supplements are quickly absorbed and appear to have fewer adverse effects compared to other performance-enhancing aids such as steroids.

GHRPs and GHRH agonists evolved from a process recently described as “reverse pharmacology,” aptly indicating the synthetic origin of these compounds. Yet, artificial peptides have shown us that the unnatural is gradually and persistently evolving into the natural.

Scientifically speaking, the term “peptide” may refer to any molecule containing 2 to 50 amino acids linked together by peptide bonds, such as collagen peptides that form the framework of larger functional proteins in connective tissues.

In the context of peptides for bodybuilding, we’re referring to a specific subset of peptides that stimulate growth hormone secretion. These peptides usually consist of a short chain of amino acids bonded together in a specific order (sequence).

Note that there are numerous peptides used in “peptide therapy” that may promote wound healing, weight loss, and muscle growth, such as body-protecting compound 157 (BPC-157). However, many of them don’t operate through growth hormone-related pathways, which is the focus of this article.

Human Growth Hormone Production and Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1

Most bodybuilders that use peptides like CJC-1295 and ipamorelin do so to increase muscle mass and fat loss by augmenting their body’s production of human growth hormone (HGH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). HGH and IGF-1 share an intimate connection since HGH is a precursor of IGF-1. However, these peptide hormones have marked differences in terms of their physiological effects.

The brain is the veritable command center of GH production. The hypothalamus secretes a peptide named growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH), which then binds to somatotrophs (GH-releasing cells) of the pituitary gland and causes them to secrete GH into the blood circulation.

HGH is predominantly a “mobilizing” hormone that liberates fatty acids from adipose tissue for use as energy. Hence, HGH is great for fat loss and preserving lean body mass (due to its anti-catabolic actions on skeletal muscle).

However, growth hormone is not intrinsically an anabolic hormone. Instead, it has indirect anabolic actions by signaling the liver to produce more IGF-1, which has potent anabolic actions throughout the body. As such, IGF-1 is a peptide of interest for muscle growth.

Most of the GH we produce occurs during deep sleep cycles, in a pulsatile fashion. As we age into our 30s, the amount of GH the body naturally produces declines significantly. Many alternative healthcare practitioners are capitalizing by proclaiming that HGH peptide therapy is the fountain of youth.

While some athletes and bodybuilders use recombinant HGH and IGF-1, these peptides are very expensive. Much more affordable GHRPs and GHRH analogs are growing in popularity as alternatives to HGH and IGF-1.

History of Peptides that Increase Growth Hormone Levels

Starting in the 1970s, researchers began focusing on a series of synthetic enkephalin opiate analogs to better understand how growth hormone (GH) works in the body. The enkephalins were studied because they are small, naturally occurring peptides of the brain that resemble the structure of opiates which are known to stimulate GH release. Therefore, scientists posited that these natural opiate peptides were related to an elusive natural growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) that remained uncharacterized at the time.

Even though opiates were suspected to induce GH secretion via a direct action in the hypothalamus rather than through the pituitary gland, and were not thought to be GHRH itself, the possibility was considered that these natural peptides might release GH through a hypothalamic and pituitary mechanism. For this reason, methionine- and leucine-enkephalin and their analogs were studied in vitro for a direct pituitary gland action.

Noteworthy was that the pentapeptide DTrp2 — related to the native methionine-enkephalin — was found to release GH in vitro but with low potency. DTrp2 was important for subsequent studies since it had a known amino acid sequence and stimulated the release of GH directly through the pituitary gland.

DTrp2 also had no opioid receptor activity and was specific in action in that it did not release thyrotropin stimulating hormone (TSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), prolactin (PRL), or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), all of which derive from the pituitary gland.

DISCOVERY OF GROWTH HORMONE-RELEASING HORMONE LED TO THE CREATION OF SERMORELIN (CJC-1295)

The paradox of DTrp2 was that it did not increase GH secretion in vivo. Since the peptide had the presumable pituitary action of the putative natural GHRH, it was considered to be a “peptidomimetic” that could be improved upon through structural modifications. (In simpler terms, scientists could rearrange the amino acids within the peptide to make the molecule more effective at activating target receptors.)

Eventually, new analogs were synthesized that had both in vitro and in vivo activity. A hallmark of these peptides was the development of a bioactive hexapeptide dubbed GHRP-6 (since it contains just six amino acids).

Initially, GHRPs were thought to mimic the growth hormone-releasing action of a newly discovered endogenous hypothalamic hormone. Over time, it became apparent from the uncoded D-amino acid residues of these unnatural peptides that the amino acid sequence of the presumed natural hormone would be different.

As such, synthetic GRHPs, which several research groups have since developed, are considered peptidomimetics (a big word for molecules that mimic the physiological effects of natural peptide hormones like human growth hormone).

The isolation of natural GHRH was accomplished in 1982 after a team of scientists extracted a then-unknown 44 amino acid peptide from a tumor that caused acromegaly (excess HGH production) in a patient. Soon thereafter, the long-acting GHRH agonist sermorelin, aka “CJC-1295” or “mod-GRF 1-29,” was created as an investigative weight-loss drug and for treating growth hormone deficiency.

Fast forward to now, many GHRPs and GHRHs exist. An issue that remains unresolved is to what degree endogenous GHRH, which may be increased by the hypothalamic action of GHRPs, mediates GH release.

Collectively, animal and human studies show that low doses of GHRPs do not increase endogenous GHRH release. Nevertheless, the data also indicate that endogenous GHRH plays only a permissive or passive role in the release of GH induced by lower doses of GHRP, rather than being the direct mediator of this release.

In contrast, high doses of GHRPs appear to increase endogenous GHRH release, suggesting that endogenous GHRH plays an active rather than a passive role in the GH released by GHRP. Recent data found that a GHRH antagonist significantly inhibited the GH response of GHRP-6 in healthy young men.

Showing 1–12 of 46 results

-

5-Amino-1MQ Peptide Sciences

-

AOD-9604 Particle Peptides

-

BACTERIOSTATIC WATER 10 ML Particle Peptides

-

BPC-157 Particle Peptides

-

BPC-157, TB-500 10mg Peptide Sciences

-

CJC-1295 + DAC Particle Peptides

-

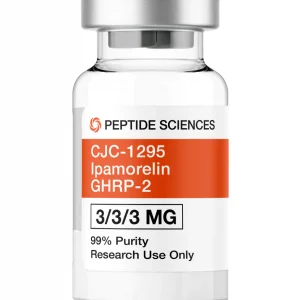

CJC-1295, GHRP-2 10mg Peptide Sciences

-

CJC-1295, GHRP-6 10mg Peptide Sciences

-

CJC-1295, Hexarelin 10mg Peptide Sciences

-

CJC-1295, Ipamorelin 10mg Peptide Sciences

-

CJC1295, Ipamorelin, GHRP-2 Peptide Sciences

-

DSIP Particle Peptides